There’s a classic way to teach relativity, where we start with the notion that all observers view light to travel at exactly c, and then work out what that means about the world. We often talk about box cars with light and mirrors, spaceships flying past one another at high speeds, and so on.

But I’ve liked to take a different approach to it, that I think tells a more fundamental story. A story where the consequence of reality is that light travels at c. And that story begins with geometry.

Part 1 will be just a refresher on basic geometry.

1. Going around in circles

We get a question frequently “what is time?” People are really mystified by the idea of time, but for some reason, no one asks “what is length?” We understand what length is, it’s the distance between here and there. My favorite definition is that “it’s what you measure with a ruler.” Obviously, it doesn’t really matter how long any one ruler is, so long as the lines on that ruler agree with other rulers used by other people.

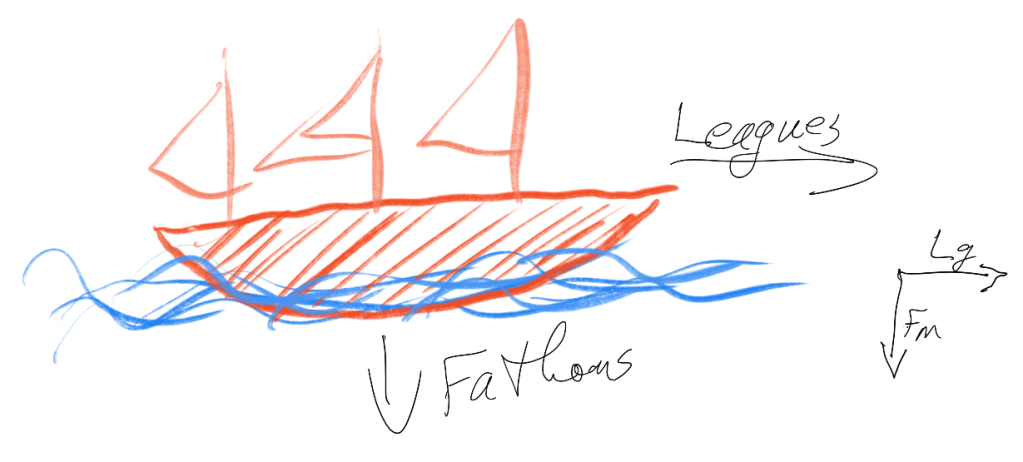

But let’s talk about an important case where two different ‘rulers’ were used in different ways. It’s a very common misconception that 20000 Leagues Under the Sea is a measure of depth, that the Nautilus is at a depth of 20,000 leagues below the surface (particularly because leagues are an archaic unit and we often don’t have a sense for how big one is). The Earth’s circumference is about 7000 leagues, so 20000 is nearly 3 times around the planet (if it travelled in a straight path around). Obviously, the Nautilus is not 20000 leagues below the surface of the water then.

The nautical terminology for depth in water would have been ‘fathoms’, and there were about 3038 fathoms in a league. Now, they used different units for good reason, there’s a lot more forward/backward/left/right space to move around, and much less in the up/down direction.

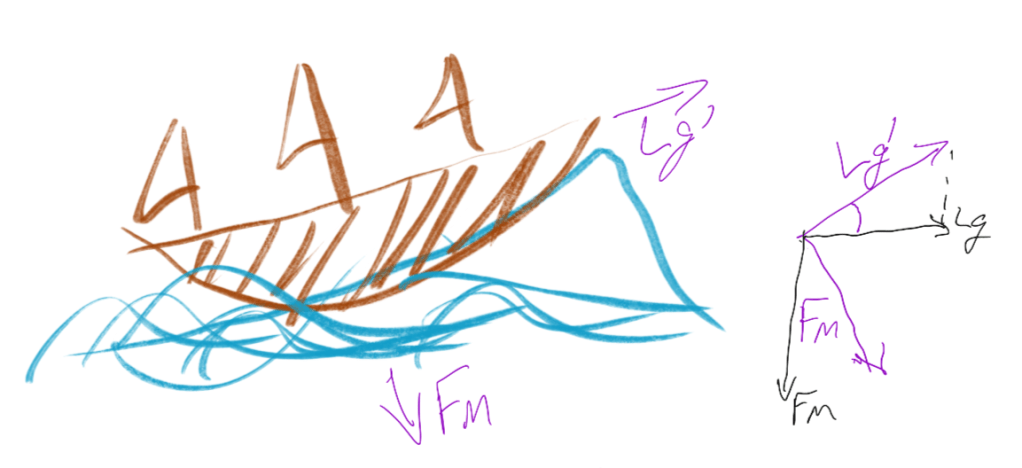

Now, let’s pin those directions to the ship: Let’s say we always measure the distance in front of the ship in leagues, and the depth pointing straight below the ship in fathoms. A big wave comes by, causing the ship to pitch up. But since we’ve pinned our directions to the ship, that now means we measure not straight across the surface of the water in leagues, but a little bit up into the air. And the measure of fathoms doesn’t point straight down to the sea floor, but it points a little bit forward now.

So, now that we’re using leagues to measure a bit up/down and fathoms a bit forward/back, we want to make some observations. Whatever units we’re using, we should make sure that distances between any points remains the same.

How do we find the distance between two points? d2=x2+y2 where d is the total distance and x and y are measurements in two directions where both of those directions form a right angle. You can tack on an extra +z2 on the right hand side if you want to talk about 3 different space dimensions. (Though we’ll keep things 2D since it’s easier to illustrate.)

For us, we can just say we want to work in fathoms for now, and let’s call ‘k’ the conversion factor that tells us how many fathoms are in a league. so we get something like d2=(kL)2+f2 . Pretty straightforward.

Now, if you’re familiar, you might recognize r2=x2+y2 as being the equation for a circle of radius ‘r’. Which makes sense. A circle is defined to be all the points that are at some distance ‘r’ away from the central point (similarly, a sphere in 3D).

I’m going to skip over the specific maths here, but for us to work in the rotated coordinate system we need to use trigonometry: sin, cos, tan. We don’t usually call it ‘circular’ trigonometry, but there is another form of trigonometry, ‘hyperbolic’ trigonometry, out there that you might remember from a calculator as sinh, cosh, tanh; we’ll come back to that later.

2. Going hyperbolic

Now we introduce a couple basic premises of relativity. As I state above, I’m taking a different approach to relativity, so these are different premises than you may usually be used to.

- Time is the same “kind of thing” as length. A clock ticking away seconds is “the same as” a ruler with centimeter ticks along it.

- Like inches and centimeters, or leagues and fathoms, we need a conversion factor.

- Time is connected to the other spatial directions in a slightly different way, and we require slightly different maths for it.

Let’s start with the first premise; the common question I skipped above. “What is time?” The answer is very unappealing to a lot of people. It is “what you measure with a clock.” That’s all. It’s not a ‘stuff’ that ‘flows’. It’s not particularly magical, which really conflicts with our sense of the world. I can look and see two objects that are 1 meter apart. I can walk over to them and get out a ruler and measure that they’re 1 meter apart. But I can’t look at two moments in time ‘at the same time.’ Hopefully I’ll get back to the details about what that means, but the short form is that that’s just the way your brain works, nothing we can do about it.

The sub-bullet: we need a conversion factor. How many meters are in a second? How many miles in an hour? How many furlongs in a fortnight? It doesn’t really matter which specific units of length and time we use, we need to have a conversion factor between them. So let’s just stick with the scientific standard of a meter and a second. There are roughly 300,000,000 meters in every second. 300,000,000 meters being equivalent to one second is the same thing as saying there are 3038 fathoms in a league. We call this unit conversion factor between lengths and times ‘c.’ Yes, of course you have always thought of it as ‘the speed of light’ but that’s just an artifact of how we came about discovering it. Its real, true meaning is that it tells us how many meters are in a second; that light travels at that speed is a consequence we’ll get to later.

The second point is the trickier bit, that space and time ‘connect’ in a slightly different way than the other space dimensions do. I think the easiest way to introduce this is to write out the formula for ‘separation’ between ‘events.’ An event is a specific point in space at a specific moment in time. If you sit still for 1 second, the equivalent of 300,000,000 meters separate you from where you were 1 second ago, those are two ‘events’ separated by 1 ‘light-second’ in space-time.

The formula is s2=-(ct)2+x2+y2+z2 . It is important to note two things. First, we’re using (ct) so that we have all the things in the same units, like above with leagues and fathoms. Second is the minus sign in front of the (ct)2 term. This is very important. You can also leave (ct) positive and subtract the three space dimensions, and I won’t deal with the details, but we call these signatures and the equation I wrote down is (-+++) and the other signature is (+—), and it’s the usual convention to put the time coordinate in the first position of the equation.

For the sake of convenience in typing, I’m going to drop off the y and z terms, and just look at distance along a line ‘x’, over time ‘t’: s2=-(ct)2+x2 . Now, you may be less familiar with this formula, but it’s the formula for a hyperbola. Below is an image of two different hyperbolae, but there are a few things to point out here.

- These are equal to 1, but as that number gets closer and closer to zero, they end up looking more and more like just the red dashed lines called ‘asymptotes’. At ‘zero,’ things are a bit messy, but let’s just say the hyperbolae are those two lines.

- In a circle, one point has no other points that are 0 distance away from the center.

- In a hyperbola, there are actually two whole lines of points that are 0 ‘distance’ away from the ‘center’

So let’s return to a notion above: you’re sitting still for a second. You have travelled 1 second, 300,000,00 meters, whatever you want to call it, in time. In fact, you are always travelling at precisely 1 second per second in time. You can’t not travel at 1 second per second in time.

The next section will add a new premise for relativity and combine it with some ideas we covered here

3.

The final premise of relativity is its namesake. All motion is relative. When we drive down the road and our car’s speedometer reads 88 km/h (55 mph), we always think of ourselves as travelling at that speed, and the Earth standing still. But that’s because we chose to pick the ground as a “still” object and measure our speed against it.

But the principle of relative motion says it is just as fine to say that you are not moving at all, and it is the earth speeding by you. And you may chuckle a bit at the thought of the Earth being the one moving by you, but consider this: if you want to toss something to another passenger in the car, you don’t throw to where that person will be in the half second it takes for the object to reach them, you toss completely normally. You toss as if you were all at rest, inside the car, even though it’s travelling at some speed.

There is one caveat here we will return to later which is that acceleration breaks this rule. You can tell when the car is accelerating, you feel pressed back into the seat. If you tossed ‘normally’ to someone, you’d possibly miss. So we’re only talking about ‘rest’ and uniform straight motion (the special case of a more general theory of relativity).

Now let’s put that together with a comment from the previous section. You, yourself, are always travelling at 1 second per second through space time. Because all motion is relative you can always say you’re the one at rest, and so all of your ‘motion’ in space-time is just in the direction of time. But someone sitting on the side of the road sees you fly by them at 88 km/h. And that someone sitting on the side of the road also sees themselves as only travelling 1 second per second through time, and not at all through space. So if they’re seeing you move with some speed through space, to them it looks a little like you’re borrowing it from your speed through time.

<To be continued…>